Around the globe the poor are living in the path of climate change. The 2017 hurricane season is far from over, and already the impact of the season’s storms has disproportionally affected the most marginalized populations in the US as well. The neighborhoods in Texas, Florida and now Puerto Rico, that will suffer the most in the aftermath of September’s storms are the areas of both the lowest income and, often, the greatest susceptibility to flooding and damage. In a small moment of good news the impact of Hurricane Irma was less “nuclear” than many had expected. Still, even as it weakened on its way through the Southeast, it left behind a trail of floods and fallen trees. While an estimated 13 million people were left without power; the worst of the physical damage occurred in the Florida Keys.

Pundits and politicians like to say that disasters don’t discriminate, and that may be true in terms of the area that a storm may sweep over. But the aftermath of these storms does put into stark relief the inequities in city planning in the areas that they strike. Disasters tend to worsen the already present inequalities in their paths. Speaking to the Christian Science Monitor, Robert Bullard, a professor at Texas Southern University in Houston and an expert on environmental justice, said about the recovery efforts in Texas, “Historically, [with] disaster recovery dollars … money follows money,”In other words, it is easier for disaster survivors with more resources to recover than those without – either because they can access aid programs more easily, or because they can afford to move away.

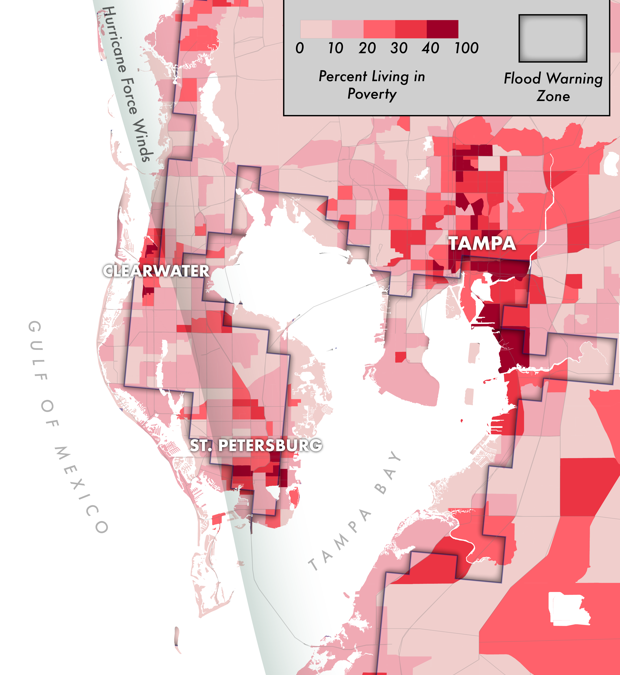

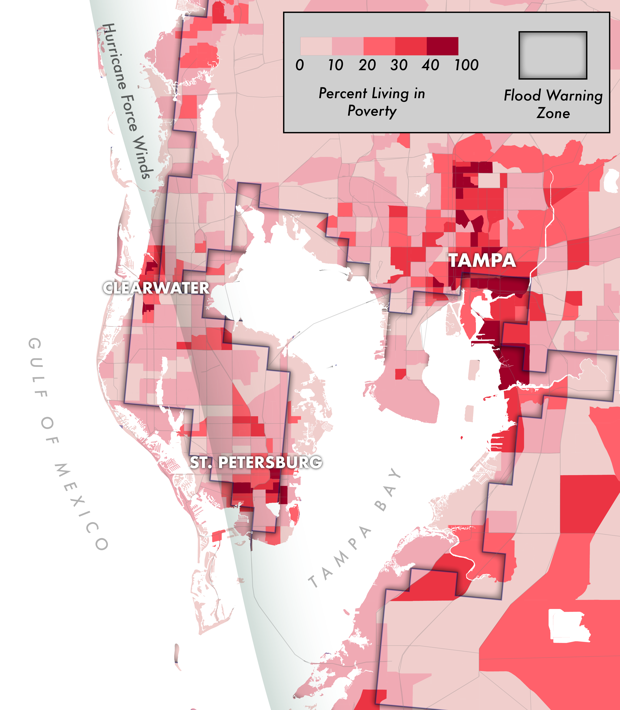

Irma hit small and vulnerable island communities in the Caribbean with all its strength, flattening buildings and causing many deaths among a population that was unable to evacuate in its path. In Texas and Florida, it’s the poor people, mostly people of color, the disabled, and the elderly—who will probably pay heavier tolls in its aftermath. CityLab mapped the concentration of low-income people of three Florida cities; Tampa Bay, in particular, was bracing itself for Irma. The Washington Post recently reported, that the region’s low-lying terrain, vulnerability to sea level rise, immense growth in population, and rapid development have created a significant risk for climate change-related disasters. Tampa dodged a major hit from the stornm, still, strong winds and heavy rain didn’t created a level of damage and flooding that will take time to repair— waterlogged streets, ruptured electrical lines, and fallen trees.

Like in other parts of Florida, the newer crop of bay front mansions and luxury apartments have flood risk in mind, while older housing in flood zones are not as secure. And pockets of poor and elderly communities live in and near flood zones, too.

This map shows the Tampa-St. Petersburg area. The deeper the red, the higher the poverty. And the zigzag line skirting the bay shows the flood watch zones:

Climate change-related flooding in some of the city’s poorer neighborhoods has gotten less attention. Liberty City, the majority-black neighborhood that served as the backdrop for Oscar-winning film Moonlight, is actually on higher ground, and therefore less vulnerable to storm surge flooding—putting it at risk for “climate gentrification.” Still, its residents were anxious about their vulnerability. “We’re in the inner city here. People don’t want to help folk like us,” a resident told the Miami Herald. “Nobody is leaving Liberty City because there’s nowhere for them to go.”

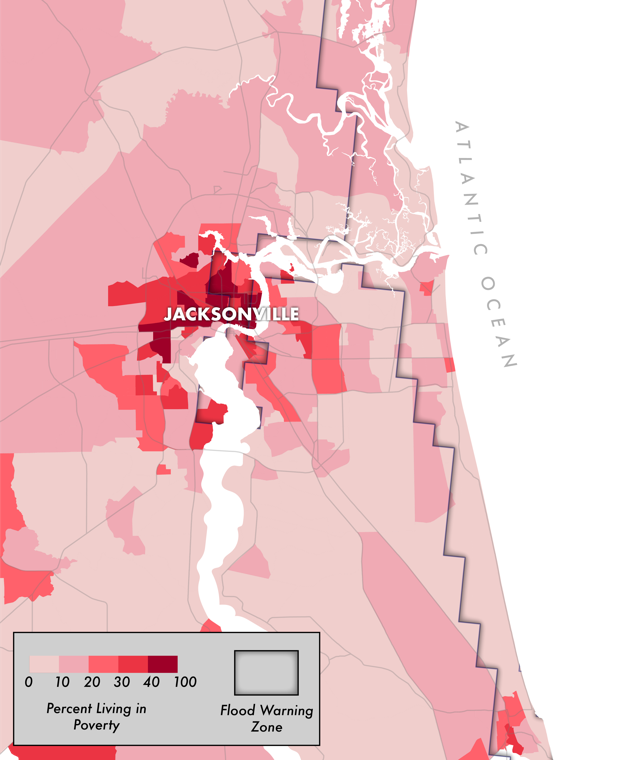

Further north, Jacksonville fared worse. The city experienced record flooding—especially, but not limited to, around the St. Johns river. According to Jacksonville.com, several working-class neighborhoods in the city’s north and its suburbs were inundated too.

The Associated Press estimated that most residents in Florida’s flood zones do not have insurance. With climate change, stronger, more unpredictable storms might become more frequent—and Florida, whose governor dismisses this threat, is particularly susceptible. Meanwhile, it’s going to become harder and harder to move its growing population out of harm’s way.