For days the smog levels in Delhi have been choking residents and threatening health with dangerous particles and an air quality index that has reached 999 (anything above 500 is considered “hazardous,” and, by comparison, the current levels in London are around 66). The inland city gets no help from sea breezes and stagnant air can linger over the area for extended periods of time.

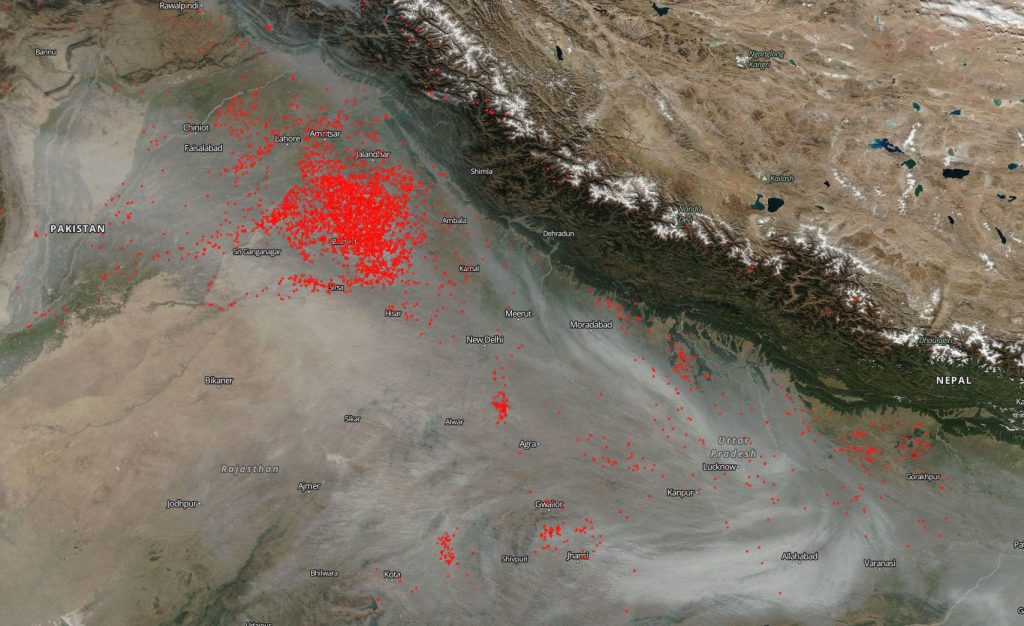

Breakneck growth combined with little regulation over the rapid industrial expansion throughout Asia and the middle east has created dangerous levels of air contamination in many urban areas, Delhi is just the latest example. Made worse in the autumn by the burning of farm land to prepare for winter planting, the Centre for Science and Environment, an advocacy network, calls this season the worst in nearly 20 years. The rampant pollution affects every aspect of life in the densely populated urban center. Industrial plants are forced to suspend operations, schools are closed, events are cancelled, automobile use is limited and health declines for all the residents.

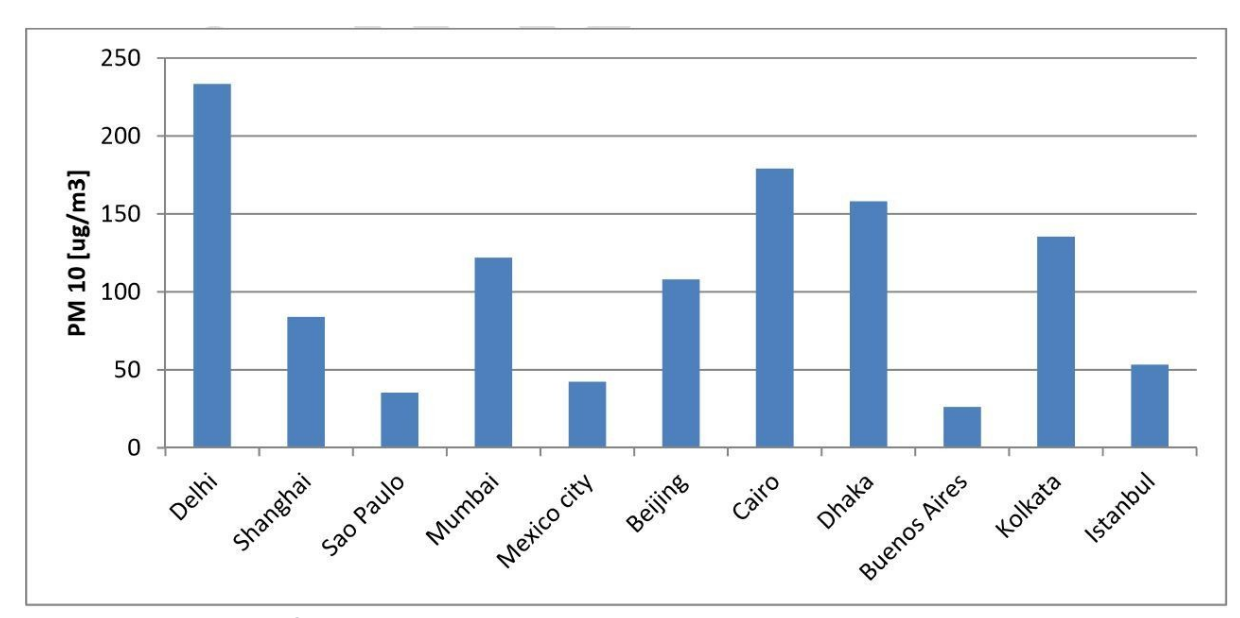

Among mega-cities (urban areas with over 14 million inhabitants) Delhi and Cairo had the highest levels of urban air pollution. Image: World Health Organization

Bhargav Krishna, who manages the Public Health Foundation of India’s environmental health center, commented that, “The diffuse nature of power means that it is easy to pass on responsibility to others.”

Among the persistent problems for policy makers is that the sources of the pollution — vehicles, construction, crop burning and holiday fireworks — fall under the authority of half a dozen city, state and federal government bodies, which are in some cases at odds with one another politically, Mr. Krishna said.

Farmers use fire to clear pests and create fertilizing ash. This image on November 8, 2016 shows fires burning in fields upwind of Delhi. Source: NASA Image

The distribution of government authority and responsibility that stymies solutions to critical global problems is the reason that GSNs are gaining importance in addressing crucial events. Taking the problem solving initiatives out of the purely political context and engaging multi-stakeholders (civil society, private sector, government and individuals) in finding solutions can often arrive at measures that governments alone cannot impose.

The director of the air pollution programs at the CSE, Anumita Roychowdhury, said,

“Unfortunately, despite the scary hard facts about the elevated cocktail of pollution and health risks, official effort to drive public policy more aggressively to reduce the daily dose of pollution and exposure, is still weak,”

The factors that need to be considered are complicated. There has been progress made in reducing emissions from transportation, but a rapid increase in the number of vehicles operating in Delhi means the increase in pollutants has slowed, but not reversed. The farmers have been instructed to delay their rice crop rotation as a water-saving measure, leaving them with fire as their most affordable method for preparing their winter fields.

The CSE feels that the “soft” options have been exhausted and they are directing their efforts to the bigger challenges. First, though, India’s people must get through the next few days.