An independent report commissioned by the World Health Organization (WHO) on their efforts against the West African Ebola Outbreak has concluded that the global health emergency response apparatus is severely lacking. The chair of the report, former Oxfam chief executive, Dame Barbara Stocking, stated that the WHO – which should be leading the global response to public health emergencies of international concern – lacks the ‘capacity and culture’ to respond effectively.

The Ebola pandemic, which first emerged in December of 2013, continues to impact Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia, and also Senegal, Mali, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. As of July 5th, 2015, there have been 27,609 reported cases and 11,261 deaths worldwide. While the outbreak continues to claim lives, the number of new cases and deaths have been in decline recently. Sierra Leone, perhaps the region most devastated by the crises, has just reported a week free of reports of new cases for the first time since the beginning of the outbreak.

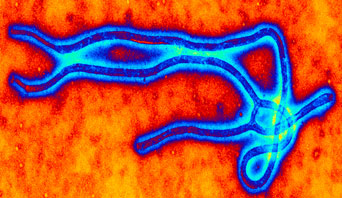

Compared to other infectious diseases such as malaria, Ebola has relatively low transmission. However, because Ebola has an extremely high mortality rate, 60% of cases in this outbreak, Ebola can create a far greater and faster death toll than other, more endemic diseases. The widespread and intense transmission of Ebola, according to the recent report, “has devastated families and communities, compromised essential civic and health services, weakened economies and isolated affected populations.”

Ebola outbreaks can be traced back to the handling of infected animals. It is not airborne, but rather is transmitted through contact with bodily fluids. In West Africa, the spread of the disease was amplified by cultural practices in burial ceremonies that involve close contact with the body. It was also transmitted through caregivers and health-care workers who were particularly vulnerable to fluid transmission in difficult field treatment centers even when protective equipment was in place. In the United States, there are 245 doctors per 100,000 people; Guinea has ten. The Economist writes that “the particular vulnerability of health-care workers to Ebola is therefore doubly tragic: as of July 5th, 2015, there had been 875 cases among medical staff in the three West African countries, and 509 deaths.”

In response to the crisis, the WHO has engaged their member states and emergency response personnel to treat and prevent Ebola cases. Their activities have included:

- training burial teams and frontline workers to protect themselves while caring for patients;

- working with communities to recognize the symptoms of Ebola early and to move their family members to care and limit contagion;

- building Ebola treatment centres;

- providing epidemiological data.

The WHO now reports that each country affected has enough treatment beds to be able to isolate and care for patients with Ebola, and the capacity to properly bury every victim known to have died of the disease. However, the WHO has also been forthcoming in admitting that their response to the outbreak was ‘slow’ and that it ‘didn’t work effectively in coordination with partners.’ This report was aimed at delving into why these issues occurred and what could be done to improve the global response to public health crises.

The WHO’s response to the Ebola outbreak fell short, a result of the organization’s politics and rigid internal culture. Despite early warnings from health personnel and NGOs working in West Africa, the WHO was late in activating emergency procedures. When the WHO began to alert to the crisis, it was slow to take action. The panel concluded that “WHO does not currently possess the capacity or organizational culture to deliver a full emergency public health response.” Elaborating, the report explains that:

WHO does not have a culture of rapid decision-making and tends to adopt a reactive, rather than a proactive approach to emergencies … WHO does not have an organizational culture that supports open and critical dialogue between senior leaders and staff or that permits risk-taking or critical approaches to decision-making. There seems to have been a hope that the crisis could be managed by good diplomacy rather than by scaling up emergency action.

The report’s recommendations are primarily aimed at internal reform of WHO, a review of the International Health Regulations (2005), the establishment of innovative financing mechanisms, and the creation of the WHO Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response.

The disregard of workers and organizations in the field in late 2013 is one of the major reasons that Ebola was able to gain such a hold in West Africa. Traditional organizations looking outwards as well as inwards could improve humanitarian response to future disease outbreaks. Ben Ramalingam, in a report for the Global Solution Networks program, found that GSNs have emerged in the wake of global health crises to “change the rules of the global health game – opening up governance structures, sharing knowledge and science, developing new products, creating markets – all with the ultimate aim of preventing and treating diseases.”

An entire ecosystem has evolved, some elements spearheaded by the WHO itself, including organizations such as the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, the Stop Transmission of Polio Program, the GAVI Alliance, and the Global Network for Neglected Tropical Diseases. These networks, unburdened by bureaucratic limits, fill the gaps left by traditional national and international public health bodies. Humanitarian networks such as the Digital Humanitarian Network have also been involved from the outset of the Ebola outbreak to provide much needed surge capacity and support in data collection, map development, translations, emergency telecommunications, and analysis.

Finding a way to integrate these emerging and powerful networks of digitally empowered health experts and crisis responders is a significant challenge. Ensuring that the efforts of networks are sustainable, ethical, and accountable is of vital importance to maintaining the integrity of emergency response so that there is not a repeat of the health crisis that has gripped Central Africa.